Featured States Using the NSPM: Michigan and Maryland

(Continued from NESP News, November 2023)

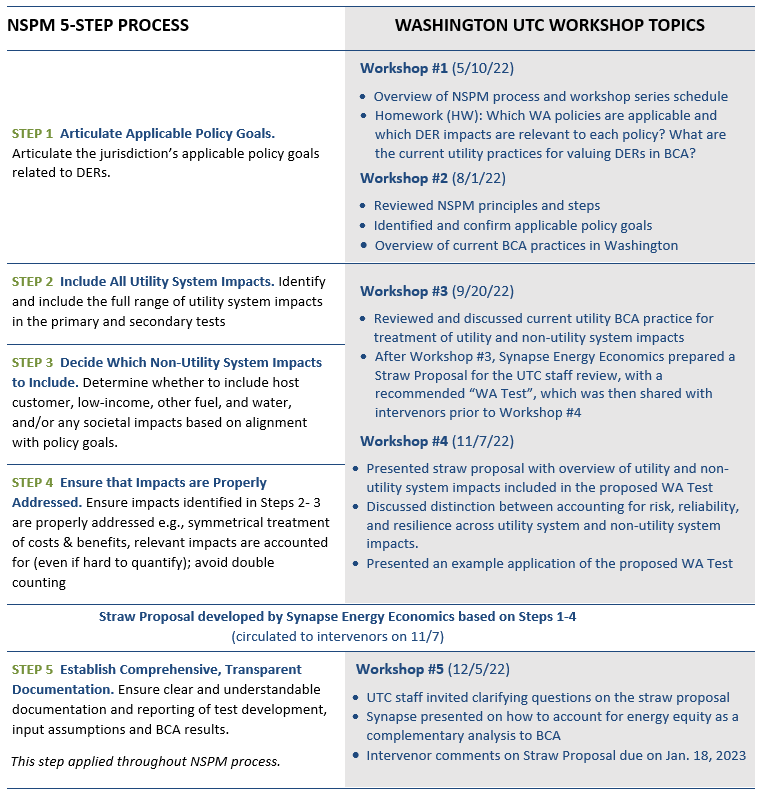

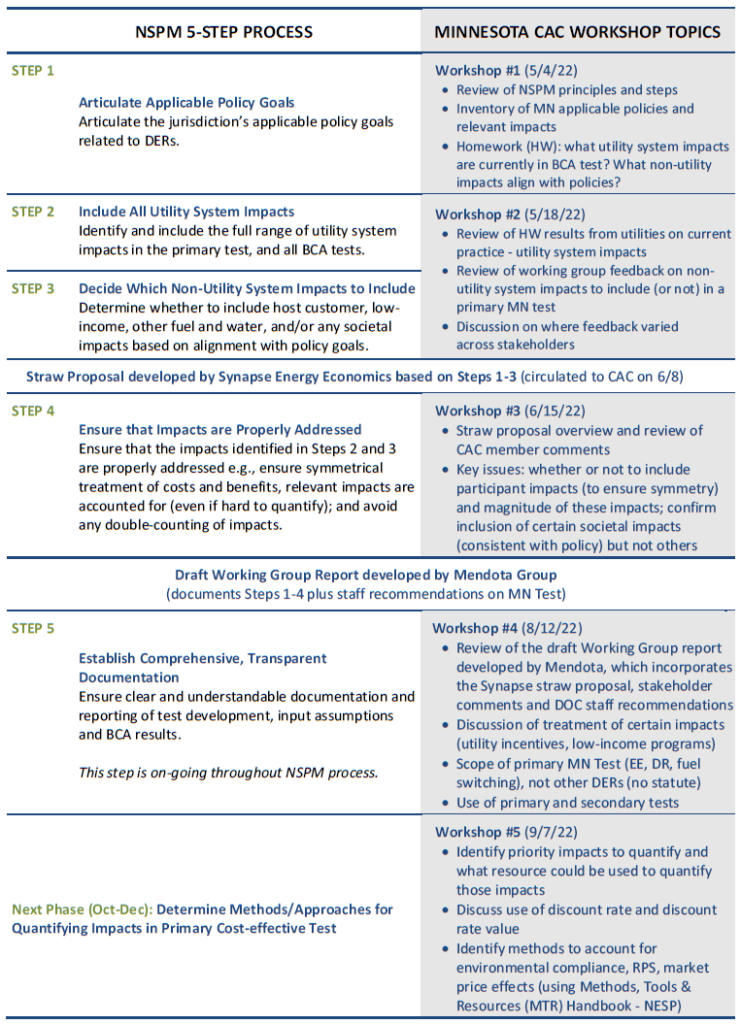

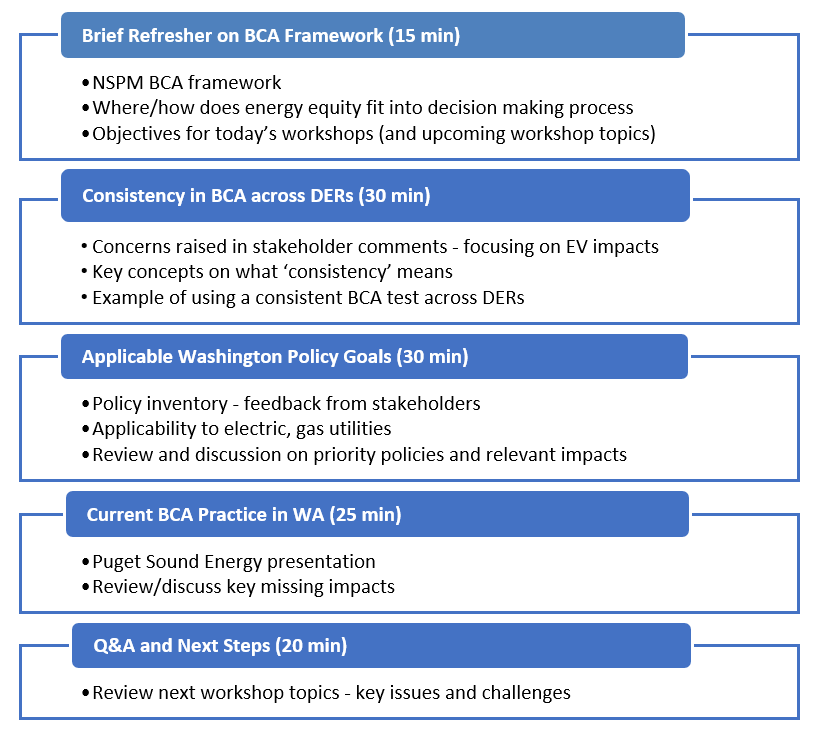

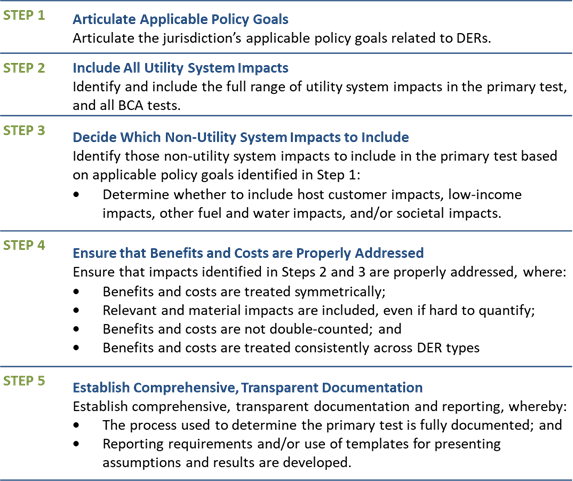

The table below summarizes each state’s approach in applying the NSPM framework. The key distinction is that in Maryland, a workgroup process is informing the development of its jurisdiction specific test (JST). Whereas in Michigan, the utilities developed a proposed JST at the direction of the commission, which stakeholders then commented on in response to a set of questions from the commission. While both states use the NSPM 5-step process, the Maryland approach involves stakeholder input throughout the multi-process, allowing for discussion of key BCA issues and with a goal of reaching consensus on which costs and benefits to include in the resulting jurisdiction specific test. Maryland’s process to date has taken longer than Michigan’s, primarily because it first updated cost tests for EVs and EE before opening the UBCA Docket 9674. Generally, however, the approach used by each state has taken (or will take) about two years from NSPM introduction to final commission orders adopting a consistent BCA test for all DERs.

| Michigan | Maryland |

| 1. NESP presentation to Commission staff and stakeholders about NSPM BCA framework in the context of distribution system planning (DSP) | 1. NESP presentation to Commission and stakeholders about NSPM BCA framework |

| 2. Commission staff make recommendation to the Commission to use the NSPM to develop a consistent BCA test for all DERs | 2. Commission directs utilities to develop BCA approach for EVs through stakeholder process, guided by NSPM |

| 3. Commission issues order for utilities to develop BCA for DER pilots guided by the NSPM. Utilities retain a consultant to develop BCA using NSPM multi-step process and files proposal with commission, recommending the proposed MI jurisdiction specific test (JST) be applied at scale. | 3. NSPM principles are applied to inform development of BCA for EVs and then to EE (EMPOWER programs). Commission approves a MD-EV JST (2021), and separately a MD-JST for EMPOWER programs (2022). Commission staff recommend that the Commission open a docket to develop a UBCA test for all DERs |

| 4. Commission invites public comment on the utilities’ proposed BCA, focusing on key questions including impacts to include in a consistent BCA test, methodologies to account for impacts, and whether to develop a transparent BCA spreadsheet tool. | 4. Commission opens docket (Jan 2022) to develop a UBCA for all DERs in range of regulatory contexts using NSPM, building on EV and EE BCAs. Requests public comment and issues order convening workgroup and issuing RFP for facilitation services. |

| 5. Interested stakeholders file comments responding to Commission’s set of questions. | 5. Commission staff select consultant to facilitate a workgroup using NSPM multi-step process, comprising up to 8 workgroup meeting (four have been completed as of mid-November) |

| 6. Commission issues order adopting a benefit-cost test based on the utilities’ proposed JST with modifications per stakeholder comments, ensuring alignment with Michigan’s energy goals. | 6. Based on workgroup input, consulting team to develop UBCA straw proposal for workgroup review and modifications, Commission staff to submit UBCA to Commission for approval (Q1 2024) |

| Timeframe: Fall 2021 – Fall 2023 | Timeframe: Spring 2021 – Winter 2024 (anticipated) |

More detail on each state process, key issues raised, and a final determination (for Michigan) is provided below.

Michigan

Case U-20898 – In the matter… to commence a collaborative to consider issues related to implementation of effective new technologies and business models. To recap previous NESP News, the Michigan Public Service Commission’s (MPSC) issued a July 2022 Order requiring the utilities to develop a Michigan specific benefit-cost test for pilot DER programs, guided by the NSPM. DTE Electric Company and Consumers Energy submitted (with support from a consultant) a joint Proposed Requirements and Further Guidance on Benefit-Cost Analyses for Pilot Initiatives using the NSPM five-step process to develop a jurisdiction specific test (JST). The MPSC requested public comments—via an April 2023 Order—focusing on six questions about the proposed utilities’ plan. Comments were submitted by utilities, the Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council (MEIBC), the Midwest Energy Efficiency Alliance (MEEA), and the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE).

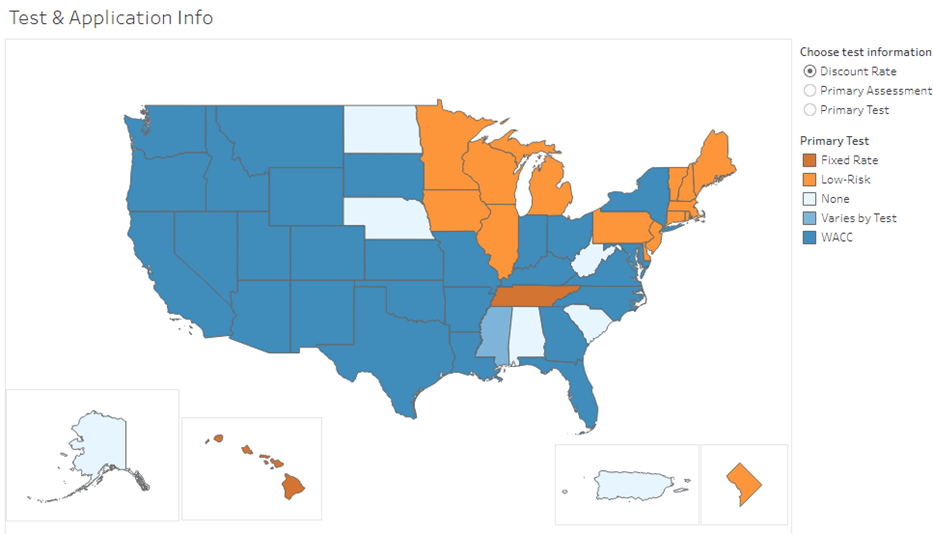

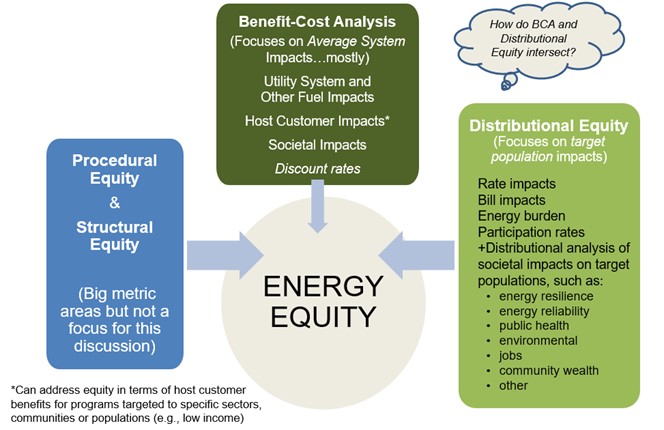

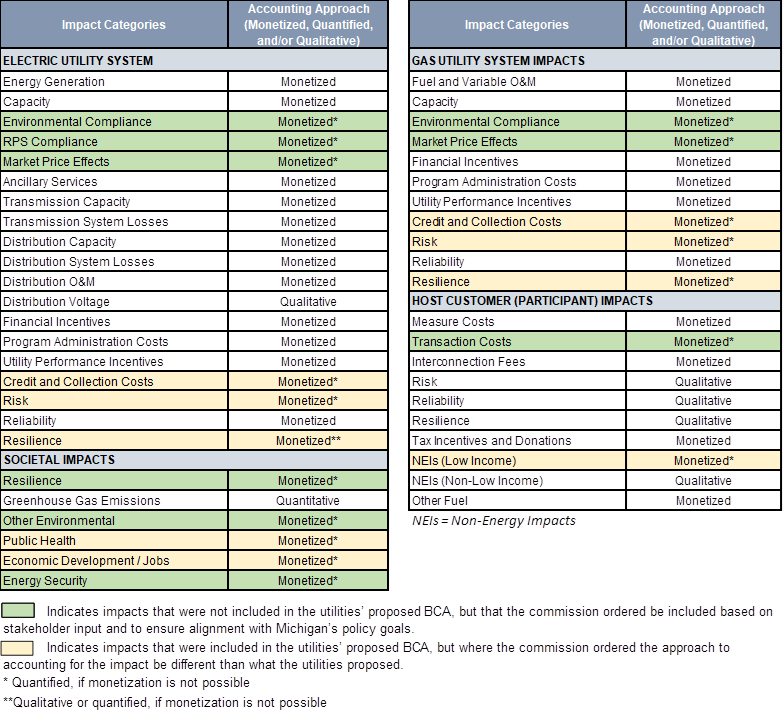

The Commission issued an October 2023 Order largely adopting the utilities’ proposed BCA test, but with changes based on intervenor comments. A summary of the BCA impacts to include in Michigan’s approved BCA JST (which the commission also refers to as the “Societal Test”) is provided in the table below, highlighting which impacts were added to ensure alignment with Michigan’s applicable policies (consistent with NSPM principles), as well as direction on methodologies for accounting for impacts—whether monetization, quantitative or qualitative. The Commission also decided on a societal discount rate from 0-3%, rather than a weighted average cost of capital (WACC), as the utilities had been ordered to develop a test based on societal impacts, rather than the impacts on a utility (for which the WACC would be more appropriate)—again, consistent with NSPM guidance.

Finally, the MPSC ordered the development of a flexible and transparent spreadsheet-based tool to measure the cost-effectiveness of DER programs, through a collaborative process including commission staff, utilities, and stakeholders. It also supported the use of additional resources such as NESP’s Methods, Tools and Resources (MTR) Handbook and forthcoming guidance on conducting a Distributional Equity Analysis (see separate article).

Commission April 2023 Order Questions:*

- Are necessary elements missing from the BCA proposal? Are there additional impact categories which should be considered?

- Are the utilities’ proposed treatment (monetized, quantitative, and qualitative) for each BCA impact appropriate?

- Is the utility proposal’s assumed after-tax WACC the appropriate discount rate to use?

- What, if any, changes to the BCA proposal are required in order for natural gas utilities to make use of the BCA proposal for pilots?

- Do stakeholders find value in the development of a spreadsheet-based tool for both the Staff and utility personnel to utilize?

- Are there regulatory examples of JST or BCA developments in other states that could be instructive for use in Michigan?

*abbreviated

Michigan’s Jurisdiction Specific Test

Maryland

The Commission opened the Unified BCA docket (Case No. 9674) in early 2022, and then convened a workgroup (Order 90212) directing utilities to issue an RFP on its behalf to retain workgroup facilitation services. E4TheFuture and its project team (comprising Energy Futures Group, Rábago Energy, Steven Schiller Consulting, and AnnDyl Policy Group) was contracted to provide facilitation and technical services to support the UBCA workgroup process. Four workgroup meetings were held from July to October 2023. The kick-off meeting reviewed the NSPM 5-step process and the commission’s directive on a UBCA framework, per its Order 90212, including that:

- “A UBCA will better align energy efficiency, demand response programs, and long-term infrastructure planning with State climate and equity efforts and encourage programs that fulfill the needs of the grid and the goals of the State.

- A UBCA framework may also assist the Commission and stakeholders to identify the least-cost means to achieve Maryland policy goals…

- The purpose of the UBCA is to better inform stakeholders and the Commission about available choices that will promote the realization of State goals and policies.

- A UBCA should also increase transparency and efficiency in the assessment of energy resources.

- The UBCA should not be designed to substitute for the utilities’ independent, experienced judgment as to how to maintain safe and reliable service on utility systems.

- The goal of developing a consistent framework does not mean that the test must be identical across different DERs and utilities. There may be impacts (benefits or costs) that are unique to a given DER. Likewise, there may be impacts (benefits or costs) that are unique to a given utility.

- Additionally, the Commission does not intend to surrender its discretion by adopting an inflexible mathematical formula that would mandate the approval or rejection of a given project.”

The workgroup reviewed a preliminary list of policies (building upon policies that informed Maryland’s development of a Statewide EV BCA Methodology and EMPOWER Maryland JST for energy efficiency), and were asked to identify priority policies that should be used to inform the development of a UBCA for all DERs, as well as any missing policies.

Maryland’s Initial List of Applicable Policies

–Clean Transportation and Energy Act of 2023 (Chapter 98 / HB 550)

–Maryland Sustainable Buildings Act of 2023 (Chapter 586 / HB 6)

–Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022 (Chapter 38 / SB 528)

–MD PSC Order No. 90261

–MD PSC Acceptance of EV BCA Framework in Case No. 9478 – PC44 ML# 238013

–PC44 Transforming Maryland’s Electric Grid

–Utility Regulation – Consideration of Climate and Labor (Chapter 614 / House Bill 298 of 2021)

–MCCC Building Energy Transition Plan (November 2021)

–The Shirley Nathan-Pulliam Health Equity Act of 2021 (Chapter 750 / SB 52)

–2030 GGRA Plan (February 2021)

–Energy Savings Goals for State Government – 2020 (Chapter 289 / HB 662)

–2020 Annual Report of the Commission on Environmental Justice and Sustainable Communities

–Clean Energy Jobs Act of 2019 (Chapter 757 / SB 516)

–Energy Storage Pilot Project Act of 2019 (Chapter 427 / SB 573)

–2020-2024 Maryland WIOA State Plan

–Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Act (GGRA) of 2016 (Chapter 11 / Senate Bill 323)

–MD PSC Order-No.-87082 from 2015

–MD Code, Public Utilities § 7–211(b) EmPOWER Act

–MD Code, Public Utilities § 7-213

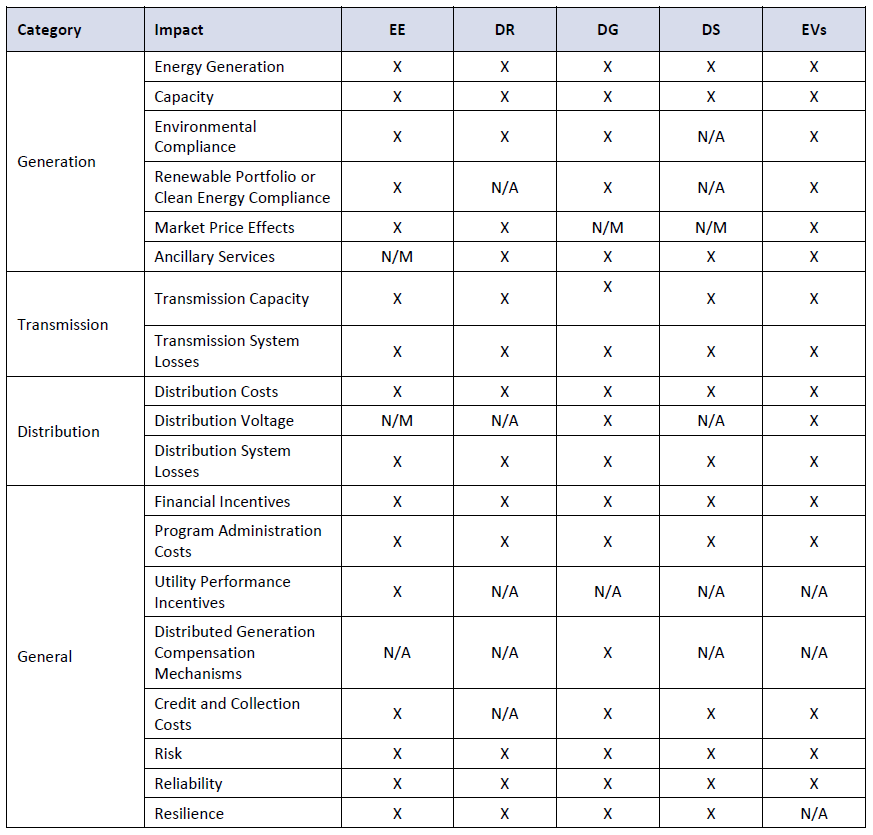

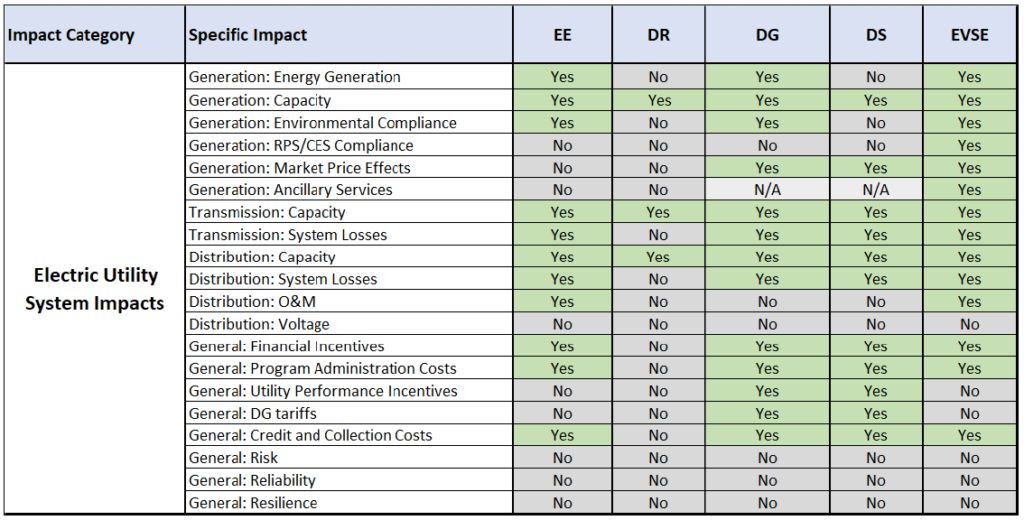

–MD Code, Environment § 1-701

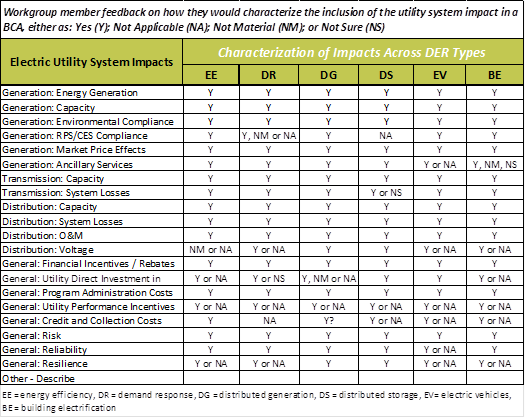

The second and third workgroup meetings reviewed utility system impacts, current BCA practice, and the applicability of impacts to different types of DERs. The table shows the collective feedback of the workgroup and how they characterized the applicability of impacts. Facilitated discussion helped to clarify key differences.

This process helped to illustrate that a consistent BCA for all DERs does not mean the same impacts apply across all DERs, but rather that the full range of utility system impacts should be part of a BCA, with transparency about which apply or do not apply, or are considered immaterial to include.

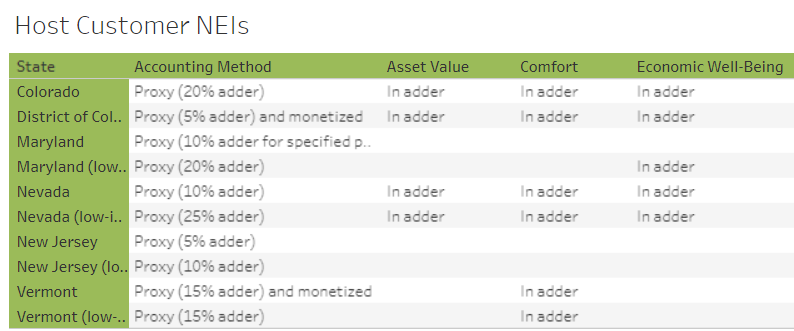

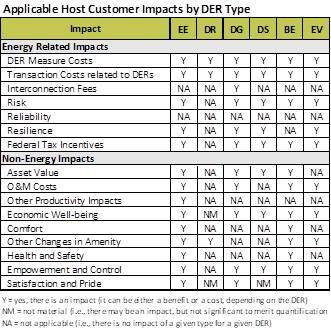

The fourth workgroup meeting reviewed non-utility system impacts (non-USIs) – i.e., other fuels, host customer, and societal impacts – and their relevance to Maryland’s applicable priority policies and to specific DERs. Discussion included the applicability of host customer (participant) impacts to different DER types, and the importance of ensuring symmetry (NSPM Principle #3) in the accounting of both host customer costs and benefits – recognizing the challenge of monetizing certain benefits – should the workgroup decide to include host customer impacts in a proposed UBCA to the commission.

The workgroup was polled on the relevance of non-USIs to the inventory of priority policy goals using the key criteria noted above; the results of workgroup feedback—with NSPM guidance—are informing a draft straw proposal being prepared by the consulting team for review and further workgroup input in December.